特別公開「Voices from Japan」No.35「Fragile structure of women’s labor hit hard by Coronavirus: The high price of “diverse working styles” in the absence of a safety net」(Mieko Takenobu)

2021/05/21・・・・・・

Fragile structure of women’s labor hit hard by Coronavirus: The high price of “diverse working styles” in the absence of a safety net(Mieko Takenobu)

The high price of “diverse working styles” in the absence of a safety net

Mieko Takenobu

In the midst of the novel coronavirus spread, the media reports every day how men are suffering from their lost employment. Facing this disaster, however, we should not overlook the situation that women are in. In the Toshikoshi Haken Mura (new year emergency relief village for temp workers) which emerged at the end of 2008, male temp workers in the manufacturing industry were spotlighted as they encountered mass layoffs in the aftermath of Lehman shock. In contrast, the novel coronavirus disaster, that spreads through interpersonal exchanges, has hit female workers who are the major employees in the face-to-face services workforce. And “diverse working styles without employment security” characteristic to Japanese society further exacerbates such impact on women.

Women are placed in a severe situation by the double punch of nationwide school closure and non-regular worker neglect

In March 2020, when the novel coronavirus pandemic started to become more acute, the number of female non-regular workers dropped rapidly by 290,000 in comparison with the same term from the previous year according to a labor force survey conducted by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. They were the sole losers, while the number of male regular workers, female regular workers, and male non-regular workers increased by 80,000, 580,000, and 20,000 respectively. The employment drop subsequently spread to male regular and non-regular workers, however the decline of non-regular female workers became far more severe, with a decrease of about 800,000 by August 2020.

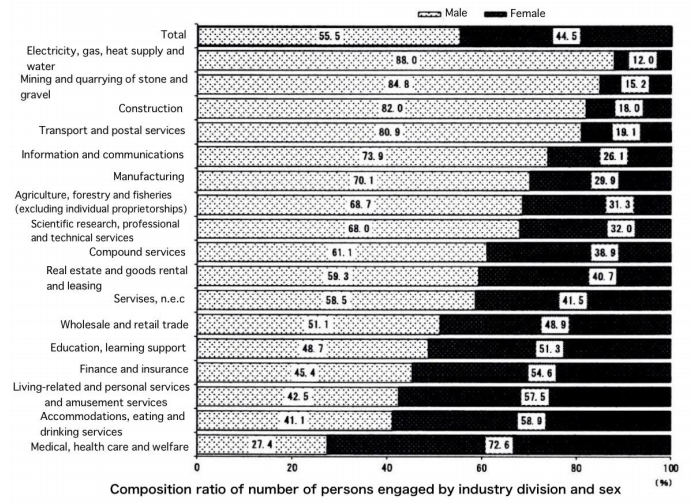

According to the 2016 economic census by the government, the medical, health care and welfare sector came out top as a workplace with a high proportion of women. Women account for more than 70% in this sector. The accommodations, eating and drinking services sector ranks second; followed by the living-related and personal services and amusement services sector; women account for nearly 60% in each sector (See the graph). The workforce has increased in the top ranking; medical, health care and welfare sector; in which newly employed workers are largely non-regular female workers. This increase is probably caused in part by the increased demand for human resources due to the spreading infection. In the second and third sectors on the other hand, business conditions have been worsening as these businesses comply with closure requests. This brought massive unemployment among non-regular female workers as the main actors in those sectors because their fixed-term labor contracts have not been renewed. Those women outnumbered the increased labor demand in the top sector, thus non-regular female workers ended up as sole losers.

An abrupt announcement of nationwide school closure request by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe on February 27 made the damage much worse. Many cries were raised from working mothers that they were unable to go to work leaving their children alone at home and thus unable to make a living. Two days later on February 29, the prime minister hurriedly announced compensation for loss of wages for families who had to take time off from work. Then a subsidy system was established to compensate workers for losses due to elementary school closures and so forth. It provided up to 8,330 yen per day and the recipients qualified to receive it were extended to cover non-regular workers.

Cries for help were from female freelancers as well who couldn’t receive either compensation for loss of wages or unemployment allowance because they were regarded as self-employed. On March 10, as the second emergency response measures came into force, the government made a decision to provide 4,100 yen per day to freelancers, approximately half the amount received by employed workers.

Despite these measures, women accounted for 60 to 70% of all labor consultations which were implemented a number of times by labor unions in the context of the novel coronavirus in March, and a labor consultation conducted by the labor counseling center of Kanagawa-Roren (federation of labor unions in Kanagawa prefecture) in February through April the results of which were released on April 21. Voices from critics were growing, claiming that it was unfair that regular employees receive 100% of the compensation for loss of wages within the coverage limit, but non-regular workers such as temporary, non-fulltime or part-time workers, receive only 60% or in some cases, nothing at all. Temp workers were also critical of the situation where the companies they are despatched to guarantee to pay leave allowance to their own employees but temp staff agencies don’t.

Thus, working women have found themselves in a double attack by the nationwide school closure, requested by the government which assumes workers do not take care of children, and the mind-set of employers who cannot imagine the need for a safety net for non-regular workers.

Serious effects on single mothers

Single parents have been affected the most seriously by this structural outline, particularly single mothers.

Non-regular workers account for 56% of working women (the average in 2019 labor force survey). Female workers aged 55 or older have a particularly high ratio of non-regular status however, also single mothers account for as high as 48.8% (2016 Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry survey) despite being in their most productive years. Non-regular workers are usually paid on an hourly or daily basis, therefore, absence from work automatically means no income. With school closure, they are forced to choose absence from work and having no income or going to work leaving their children alone at home.

A survey titled “Novel coronavirus: worsening hardships in the life of single mother households—prompt report of fact-finding survey of 1,800 mothers” revealed the difficulties faced by single mothers. It was jointly conducted by Chisa Fujiwara, professor of Hosei University and other researchers; and Single Mothers Forum, an NPO which is a self-help group of single parents.

In this survey, 70.8% answered that they were affected by coronavirus in terms of their employment and income. However, only 52.5% of regular workers responded that they were affected but this increased to 75.2% of non-regular workers and 95.5% of self-employed people, freelancers and so on; it is apparent that the damage becomes more serious when the form of employment becomes more unstable. The survey showed, from February to July 2020, respondents’ average savings declined by about 40,000 yen and the number of households in debt increased. Moreover, 10% fell behind in their rent and/or utility bills. Under such circumstances, as much as 60% of mothers reported having psychological stress.

The NPO received heartfelt comments about their Emergency Rice Aid Project intended for single mothers who suffered from increased food expenditure for daily lunch for their children because of no school lunch due to the closure, “The money that I was planning to buy rice with can be used for other food,” or “I can restart 3 meals a day, instead of 2 in the previous months,” or “now I can cook rice as usual, no need to cook rice porridge (to increase the quantity simply by adding water).”

“Husbands” are the safety net

Behind this situation, there is a mechanism characteristic to Japan that government assistance tends to be delivered to families through companies from which the family member receives pay, or husbands. One clear example is the Employment Adjustment Subsidy.

Using the fund of unemployment insurance, this system subsidizes a part of the expenses for the leave allowance for employers whose business conditions deteriorate but maintain employment of workers instead of laying them off. This is to prevent abusive layoffs so that social unrest or economic downturn would not happen. The problem is the mechanism of this system means that the subsidies are never paid unless the employers apply for it.

This is fatal, particularly for women. In Japanese society, the perception that it’s fine for women to depend on their fathers or husbands as their safety net is entrenched, not all employers are willing to take the trouble of completing the complicated procedure to apply for the subsidy for non-regular female workers.

There is a support system though, that workers can apply for directly by themselves—unemployment benefits. This, however, poses a significant hurdle for female non-regular workers to overcome. To be eligible for unemployment benefits, workers should be enrolled in the unemployment insurance scheme in the first place. The requirement of eligibility is working 20 hours a week and a prospect of over 31 days of employment. But recently, employers are noticeably reluctant to bear the expenses for social insurance for employees and they have been increasing part-time employment of less than 20 hours a week.

Under these circumstances, single mothers, among others, are forced to accept part-time jobs because of inability to work overtime due to childcare. It is not rare that single mothers have 3 to 4 different part-time jobs with less than 20 hours a week working time each, so they can feed their families. This means that even if actual working hours are over 40 hours a week, they are not covered by insurance.

To make things worse, while unemployment benefits are provided immediately for applicants who have been fired by their employers, a 3-month waiting period is necessary for those who have quit their jobs for their own reasons. Many non-regular workers are facing the situation of not having their fixed-term labor contracts renewed and it is somehow easy to be categorized as “retirement for personal reasons.” Although there have recently been some cases considered as real layoffs when the contract is not renewed after long-term working with repeated renewals, still today many non-regular workers have to wait before they start receiving the benefits.

“Such unfavorable treatment toward non-regular workers has not been addressed. Underlying this is the unconsciously institutionalized gender mindset that men, not the government or companies, provide a safety net for women. In other words, husbands (men) are guaranteed to work as regular employees with unemployment benefits and leave allowance, and through them, money is diverted to wives (women).

However, as companies began to notice the “low cost” merits of non-regular employment and men became affected by this as well, the fragility of such a safety net has caused impoverishment and instability of the entire society at the exact period, the Covid-19 disaster struck.

A special relief fund called “fixed-sum stipend” which supplied 100,000 yen equally to every individual was introduced. It specified that the authorized recipients were heads of households. This makes obvious the notion that support ought to be via husbands. The notification issued by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare regarding the national health insurance program states that heads of households shall be the major breadwinner. As a result, heads of households are predominantly male, reflecting the wage gap between men and women. It is a mechanism in which the economic gap of men and women is further amplified by the manner in which relief funds are provided. Support groups for survivors of domestic violence demanded that this mechanism be changed and a way to receive the money privately has been barely secured for fleeing survivors. Nonetheless, government mishandling was blamed for the failure to supply assistance to individuals in need. With the hashtag #世帯主ではなく個人に給付して(Relief fund to individuals, not to household heads), many comments were posted on the Internet like “Do the procedure for household separation of resident registration if you are at risk of being robbed of your money.”

Impermissible government-led discrimination

The government temporarily excluded bars and restaurants that provide companions and businesses providing sexual services from work leave compensation when the nationwide school closure was enforced. These businesses have been perceived as the funding source for antisocial forces and have conventionally been excluded from labor-related assistance such as the Employment Adjustment Subsidy. As an extension of this, the government excluded them this time too.

When it comes to the prevention of infection, however, protection of women workers who are prone to infection through their services should have been the priority rather than the source of businesses funds.

Increasingly criticized as occupational discrimination, the exclusion was retracted on April 7, 2020. These businesses were rendered eligible for the cash benefit of 100,000 yen, called “fixed-sum stipend” that the government subsequently introduced.

However, these government responses had a lasting effect. Hitoshi Matsumoto, a popular TV personality appeared on a tabloid show on Fuji TV and made this comment “Using our tax money to pay for bar hostesses’ vacation? Compensating their whole income? Excuse me, no way!” on March 5. The number of postings on Twitter or other social media, saying things like “What’s wrong with the exclusion?” has increased and that is still continuing today.

Eriko Fuse, the chair of Cabaret Club Union states “The exclusion policy was retracted but the issue remains unsolved.” Among those women workers, a fear of being exposed to severe bashing if they receive leave allowance has been growing due to the impact of the discriminatory remarks on social media. As a result, Fuse relates, many women don’t receive the allowance and instead are forced to work discreetly in another cabaret club which doesn’t obey closure requests or move to the sex industry; or are compelled to return to their parents’ home in a remote area as a jobless person.

It can be concluded that the initial response of the government that led to discrimination by treating these women as a funding source for gang groups instead of protecting them as workers, has actually resulted in the spread of infection.

Non-regularization of essential workers

Amidst the spreading infection, essential workers have been spotlighted. Examples are workers in health care, childcare, nursing, or consultation for domestic violence or child abuse who cannot close their services to support the community. These face-to-face public services require skills of care in which women are the major pillars. Because of working face-to-face, these working places have been exposed to risk of infection regardless of whether workers are regular or non-regular. Concerns have been raised by pregnant female workers in the health fields, such as “I’m so afraid of being infected but it’s almost impossible to take leave.” The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare requested employers to make consideration for workplace environment and employees, however this request failed to reach a number of workplaces which were facing a labor shortage in the midst of spreading infection. Labour Lawyers Association of Japan issued an emergency statement on May 15, calling for improvement of the leave system for pregnant female workers.

These public service workers have been a main target of non-regularization which is intended for labor cost reduction since the Koizumi Cabinet’s structural economic reforms in the 2000s. They are sometimes called “government-made working poor” subjected to lower wages and precarious employment. Women account for three fourths of such workers. Furthermore, a new system, fiscal year appointment personnel was introduced in April 2020, under which public service employees are to be hired on a one-year contract. This virtually legalized discriminatory treatment for non-regular public service employees. And it perpetuated their low wages and precarious employment, although they are the workers in charge of providing assistance for local residents. And then, the expanding novel coronavirus infection amplified their workload.

Particularly distressing is the discriminatory treatment against non-regular public service employees with respect to safety and hygiene. More than 180 people responded in approximately two weeks to the “Survey on the impacts of Covid-19 on public service workers” that an NPO named “Study Group of Government-made Working Poor” started on May 2020. More than 70% of the respondents were female non-regular public service employees who work in a range of fields from childcare, nursing, after-school childcare, to office work at schools. They reported many cases of risks such as working in a closed space and/or a crowded place and/or a close contact situation; face-to-face work with no facemasks; and no access to staggered working hours.

Public service is a sector that often involves community care for residents and can be described as “the front line” in this coronavirus disaster. However, the sector has been subjected to lower working conditions because of the prejudice against the menial work carried out by women. And now it becomes clear that women working there are being left with insufficient protection against infection and scarce benefits to compensate the increased burdens imposed on them.

“Diverse Working Styles” policy and deterioration of employment

The root cause of the distressing state of women working under the spreading of novel coronavirus is the “Diverse Work Styles” policy that the government has been promoting.

Contrary to its name, this policy is based on fixed gender roles where women shoulder all deeds supporting human lives such as childcare, nursing, and community activities. In addition to this, women workers may also experience pregnancy and giving birth. Therefore, for working women, flexibility that allows them to adjust working hours or style to fit their life is crucial.

Dutch labor law, known even in Japan, teaches us the merits of such diverse working style. In 1996, the Netherlands prohibited “working-hour-based discrimination” such as cutting hourly pay or irrationally different treatment with respect to social insurance or pension because of workers’ fewer working hours. It can protect workers with shorter working hours due to family responsibilities including childcare, from disadvantageous treatment. Further, lest employers should cut working hours at their own convenience, the Working Hours Adjustment Act was established in 2000 to provide for workers’ right to decide their own working hours.

The misfortune of Japanese women is the incoherent structure of the “diverse working styles” policy which means almost the direct opposite “deterioration of working style.” This has been established in the midst of successive relaxation of employment regulations since the 1980s.

Specifically, there are several steps as follows. First, a mechanism has been created that when women deviate from the position of ‘regular employee,’ where male workers are standard and subject to long-hours of work and relocation, they should be dropped from the safety net for workers too. Second, the government has touted diversified employment as a benefit to women and steered them to non-regular employment. Third, the fragility of the social security system has been covered up with a sense of discrimination deriving from the patriarchal “Ie (household)” system which once existed in this country, with mindsets such as “women have no problem living because they have their husbands as their safety net.” Fourth, diversity has been positioned as part of corporate human resource management and workers’ demands to ensure their rights to choose their work styles has been left behind.

The Freelance Association, a sectoral group of freelancers, made a statement regarding the amount of leave compensation for the school closure that “For freelancers, receiving leave compensation equivalent to the level of full-time employees would be too much” because “The majority of those who are on leave are women and not the breadwinner of the household.” This shows the reality that freelancers themselves are preoccupied by the third notion mentioned above.

Working women have been steadily weakened and on top of that Covid-19 broke out. Its severe impact is urging us to go beyond mere manuals on the prevention of the infection and into a structural transformation, namely, diversity accompanied by a safety net.

Mieko Takenobu, Journalist, Professor emeritus of Wako University

Translated by Akiko Kuroe

・・・・・・

「f visions」No.1のなかから、記事英訳、編集しました。

- Gendered impacts of Covid-19 in Japan: An overview (Hisako Motoyama)

- Invisibilization of dangers: What the pandemic and the nuclear disaster have in common (Nanako Shimizu)

- Fragile structure of women’s labor hit hard by Coronavirus: The high price of “diverse working styles” in the absence of a safety net (Mieko Takenobu)

- Novel coronavirus and the care sites: What will female nursing-care workers, who are at the front-line of saving lives, pass on to the future? (Asako Shirasaki)

- The reconfiguration of the gender order through handmade masks: Between handwork and science (Nozomi Mizushima/Akiko Yamasaki)

- Repeated discrimination against the sex industry regarding Covid-19 countermeasures compensation money (Sayaka Arimatsu)

- AJWRC INFORMATION 170 marched in protest against violence and exclusion of homeless woman (Hisako Motoyama)

- Major activities of AJWRC: April 2020 to March 2021

・・・・・・